"As an engineer, I often ask myself: is more precision any good?"

Tolerance is part of everyday life for engineers like Fred Baumeyer, Head of Structural Engineering at Basler & Hofmann. And it's not just about technical tolerances. Tolerance is also required when something unexpected happens on a construction site or when solutions need to be found in negotiations. In this interview, he tells us about the different types of tolerances that his life as an engineer has taught him.

Fred, what does tolerance mean to you?

Fred: Tolerance is about buffers, leeway, fit. Tolerance takes place at the interface between two systems: It's about things that are supposed to fit together. The margin - the tolerance - is the area in which the fit is still possible, despite deviation from the precise target dimension. If the margin is exceeded, things may no longer work. We engineers have to define technical tolerances for components, dimensions and rotations in every project. We adhere to the SIA standard 414 for dimensional tolerances.

In my professional life, I have also learned a lot about social tolerance. If, for example, a new IT tool is introduced whose added value is not immediately apparent to me, but which is fundamental to the overall company collaboration, I have to tolerate it first. And there is a third aspect of tolerance: tolerance of frustration is also important and can even be positive.

When is frustration tolerance important?

Fred: Frustration tolerance is about being able to endure. I'm referring primarily to acquisition. As engineering teams, we take part in many competitions and we don't always make it one round further. You also have to be able to accept rejection. Good work alone is sometimes not enough, luck and bad luck are also part of it. A rejection should not always be seen as a defeat. Instead of despairing, it is important to develop a certain systemic tolerance in order to look ahead with renewed strength. That has always paid off so far.

Has it ever happened in your career that tolerance was decisive for success or failure?

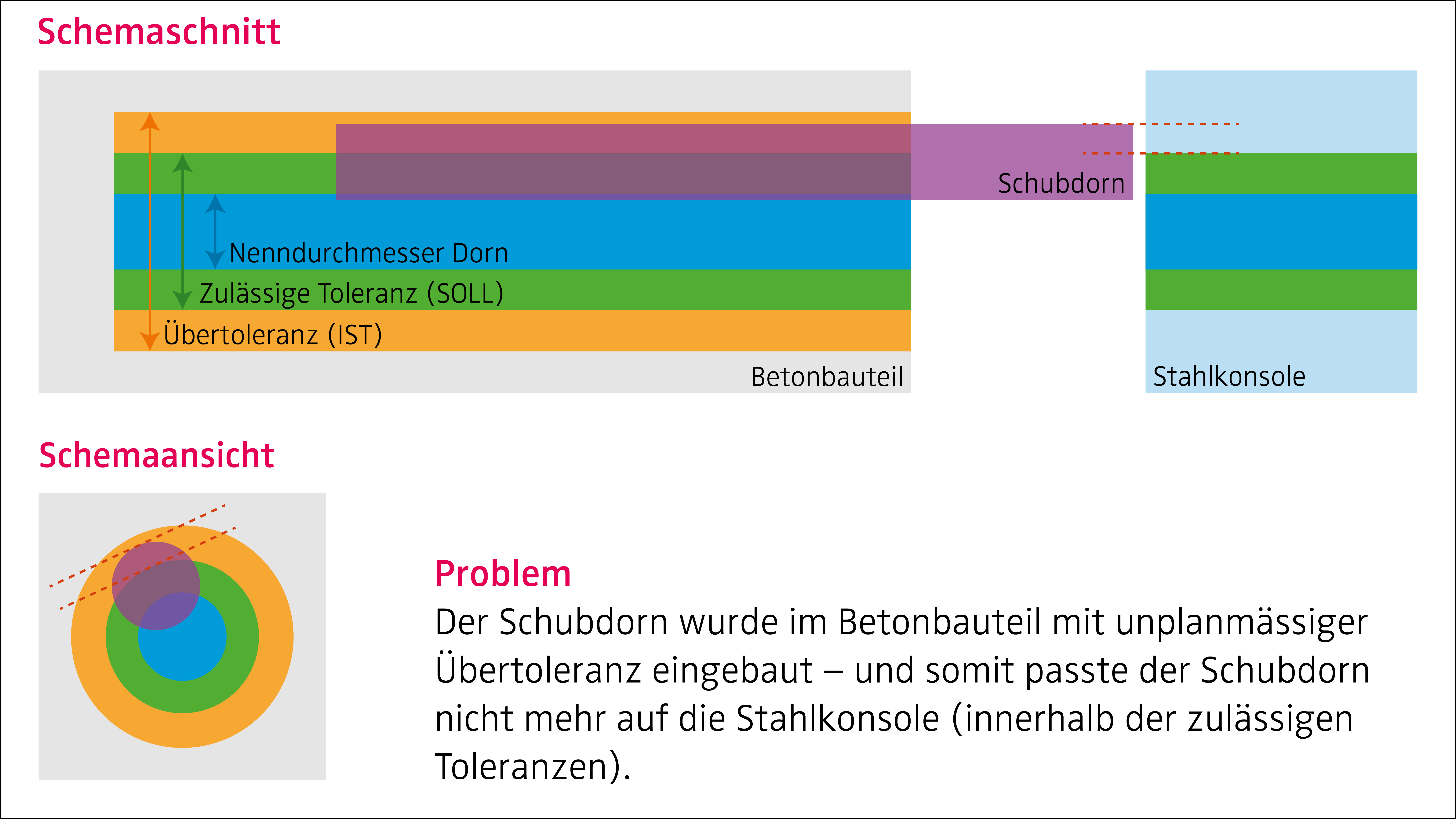

Fred: Yes, tolerance in a technical sense on a large concept design near Lucerne. Around 100 prefabricated balconies were to be installed on a residential building. The contractor unexpectedly increased the tolerances in the perforated slab for the ceiling insert. When the counter plates of the balcony elements were to be fitted, they had too much play.

Emotions ran high and the question of responsibility was raised. At first it wasn't clear why the elements didn't fit. Once the cause was clarified, we came up with an ingenious solution. We managed to adjust the holes with special mortar so that a stable connection between the panels was possible. We had to test, create a prototype and carry out measurements until we were able to implement the solution - an annular gap filling.

Emotions ran high. How do you react in such moments?

Fred: By constructively putting the "fish on the table". In other words: address the challenge and look for solutions together. In engineering, we are often confronted with emotions, because buildings usually involve major risks, a lot of money and time pressure. In this case, all parties involved finally sat down at the same table. We created a common understanding of what the facts are and what precision is required. In the end, we found a technical solution that was also within the tolerance range in terms of cost. Demanding tolerances is often crucial for conflict resolution.

Precision and leeway both play a role in your job. Which side do you feel more comfortable on?

Fred: That depends. I like the quote: "It's better to be roughly right than exactly wrong". When a young engineer says: "We need to do the math again more precisely", I prick up my ears. Is it perhaps just a matter of delaying a decision? As an engineer, I often ask myself: is more precision of any use? For example, there is no point in calculating an existing beam even more precisely if it is already clear from the rules of thumb that it obviously does not need to be reinforced. There are situations where it doesn't matter how precisely you calculate. I take the view that only as much precision is needed to stay within the tolerance limits.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa has obviously overloaded the tolerance limits of the ground. If you were allowed to renovate the tower, would you straighten it?

Fred: For me as an engineer, the sight of an unintentionally leaning structure is somewhat disconcerting. But if we ignore the fact that it is a World Heritage Site worthy of protection, as an engineer I would proceed as follows: first ask the client what they want. Then think in terms of scenarios, make calculations and derive limit values. Our team would sound out the variants and identify the parameters, risks, opportunities and costs relevant to the decision so that the client can make a good decision. This is precisely our job: to create the foundations so that those who can and must decide can make a well-founded and sustainable decision. It often takes patience, confidence and tolerance to get there.

![[English] Building Award 2023: Young Professional Award](/fileadmin/user_upload/basler-hofmann/Impulse/News/23-06-16_Building_Award_2023_Lea_Bressan.jpg)