"Nowadays, almost anything can be built"

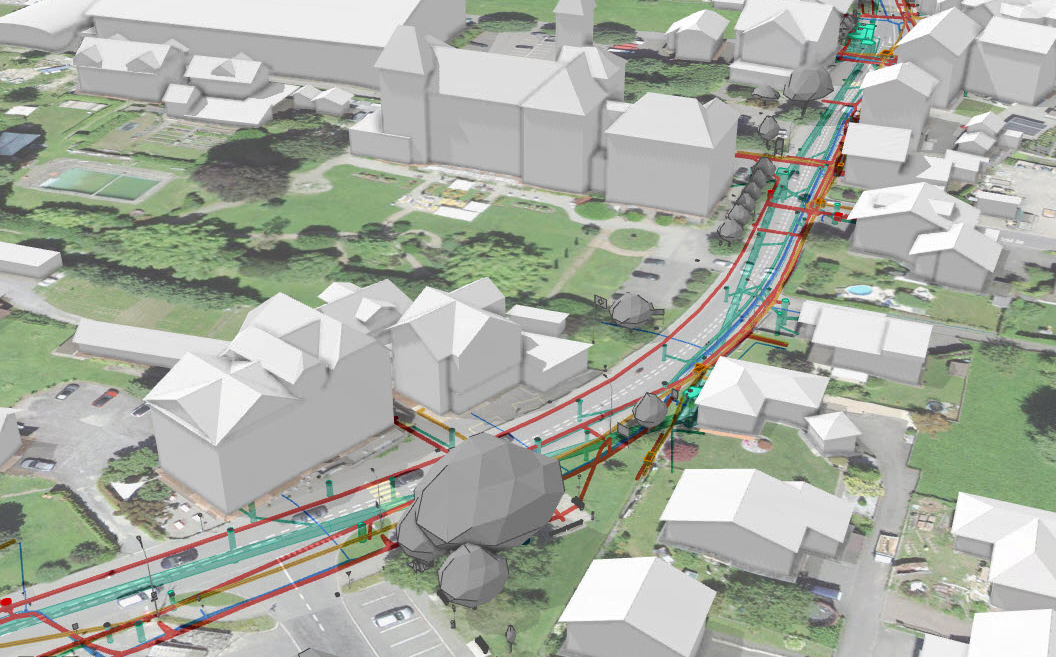

Marco Ramoni has advised clients around the world on underground construction projects. At Basler & Hofmann, he and his team are responsible for planning large-scale projects such as the expansion of the RBS railway station in Bern. In our interview on the topic of 'tolerance', Marco discusses the significant changes that have occurred in tunnel construction since its early days. The advances in feasibility and safety, as well as in relation to women's issues, are remarkable.

Marco, in which area is greater tolerance required: tunnel or building construction?

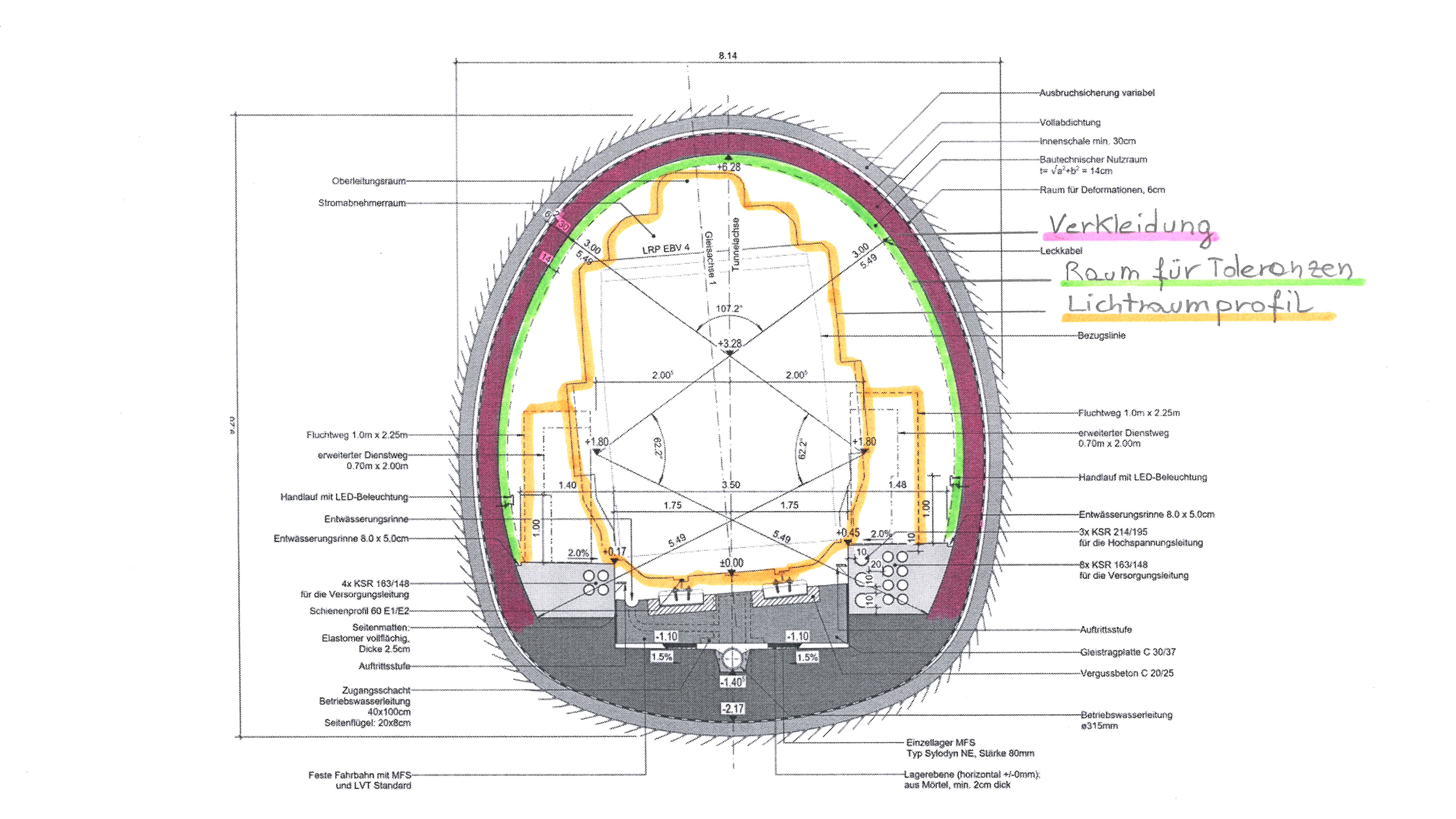

Marco: Building construction has stricter technical tolerances. They work with smaller scales where it's more a matter of millimetres. In tunnel construction, the aim is to ensure the tunnel is large enough and in the right place, while taking construction tolerances into account.

When designing a railway tunnel, for example, you have to consider the track geometry and clearance profile. These define the tunnel's location and size. However, you can't expect any contractor to work with millimetre precision — nobody can do that. That's why we build the tunnel slightly bigger, allowing for unavoidable construction deviations while still offering enough space for the train and infrastructure. We allow for construction tolerances of 10 to 15 centimetres in total.

Are there intolerances in tunnelling?

Marco: I can tell you an anecdote about that. In the early 1980s, one of my predecessors visited a tunnel construction site with a female engineer. The miners ran out of the tunnel and shouted, "A woman in the tunnel! That brings bad luck!' That was an example of intolerance back then. The only woman who was permitted in the tunnel was Saint Barbara, the patron saint. Fortunately, those days are over. Nowadays, women can be site managers and chief construction managers too.

A blatant example - are there any current no-go's?

Marco: TWhen it comes to safety, there can be no compromises. This applies to occupational safety, structural safety, and serviceability. The relevant normative requirements must be met. Occupational safety concerns human lives: nobody must be harmed. The supporting structure must remain stable under load. Serviceability means that the tunnel can be used for its intended purpose; for example, it should not deform, crack or leak.

What do you actually need to build a tunnel?

Marco: A building permit.

Are there no restrictions, such as those imposed by nature?

Marco: Nowadays, with all the technology available, almost anything can be built. It's just a question of how much it costs and how long it takes. For example, I am supervising a project in Bern for the Bern-Solothurn regional transport system, where two large caverns were excavated just 12 metres below the tracks of the SBB railway station while trains continued to run above. There are even crazier projects internationally: rivers have been crossed, even the sea.

You couldn't build a tunnel in a sand dune.

Marco: Yes, you could, you just need suitable auxiliary construction measures and the right excavation protection.

If you could travel through time and visit a tunnel construction project, which would you choose?

Marco: One option would be to observe the construction of the Gotthard railway tunnel towards the end of the 19th century. This was a pioneering era, when the first Alpine crossings were made. Much of the work was done by hand, as were the calculations. There were no computers, lasers or concrete. Where necessary, rock was supported with wooden beams. The working conditions were anything but fun for the miners, but the engineer was still the hero in the village.

Marco: It would also be exciting to visit the second era of Swiss tunnel construction, in the 1960s. Tunnels were being built everywhere, especially for motorways. Technical advances were significant, and I would argue that modern tunnel construction began at that time. My father was one of the miners who built these tunnels. He used to tell lots of stories, like how the first shower he ever saw was on the construction site, not at home. There was meat to eat every day on the construction site, and he was paid his wages — 500 francs — in an envelope. However, occupational safety culture was very different back then. My father told me about fatal accidents.

Fatal accidents back in the 1960s?

Marco: Yes, that was normal. But it was better than in the pioneering days. When the Gotthard Rail Tunnels were built before 1900, there were still more than ten fatalities per kilometer. With the Gotthard Road Tunnels, which were built in the 1970s, it was still one death per kilometer - also still a lot. Then, for the Gotthard Base Tunnel, which was built twice in the 2000s over a distance of 57 kilometres, there were a total of 19 fatalities. Today, occupational safety is extremely important. And rightly so.

How do you manage to get two tunnel boring machines to meet right in the middle of the mountain?

Marco: There are many factors involved. As civil engineers, we plan the axis on which the TBM is to travel. The surveyors then mark out the axis on site and program the TBM. Although it is computer-controlled, even such a machine cannot always travel perfectly along the axis. This is why it has an operator, who corrects it when it deviates slightly. The operator ensures that the TBM remains within the tolerances that we have calculated in advance. In addition, the contractor carries out regular control measurements and an independent surveyor, working for the client, also takes random samples. Despite all this, the so-called breakthrough error still occurs at the end.

Is there always a breakthrough error?

Marco: There is always a breakthrough error. It's impossible for two drills to meet with millimetre precision after advancing a kilometre into the mountain. But this deviation is taken into account. We're only talking about a few centimetres here. The trick is to plan in such a way that these deviations are still possible – just in case.