«Nothing that could be contaminated must be allowed to escape»

Gesche Bernhard is a biosafety expert at Basler & Hofmann. She knows how to work with potentially dangerous organisms. As part of a four-person team, she advises organizations worldwide that want to check or increase their biosafety or plan new builds and conversions of laboratories and facilities. In this interview, she explains how tolerance plays a role in her job - and what challenges she encounters in other countries.

Gesche Bernhard and her colleagues in the biosafety team combine knowledge from biosafety, engineering and laboratory safety, veterinary medicine, diagnostics, biomedicine and pharmaceutical development and production. She herself is a microbiologist and biochemist and worked in basic biomedical research, innovation development and the pharmaceutical industry before joining Basler & Hofmann.

Gesche, are you ever seen in protective clothing?

Gesche: I usually work in normal clothes at the PC or in workshops with customers. But sometimes I wear protective equipment. When we go into a research laboratory, for example, protective equipment appropriate to the safety level is mandatory.

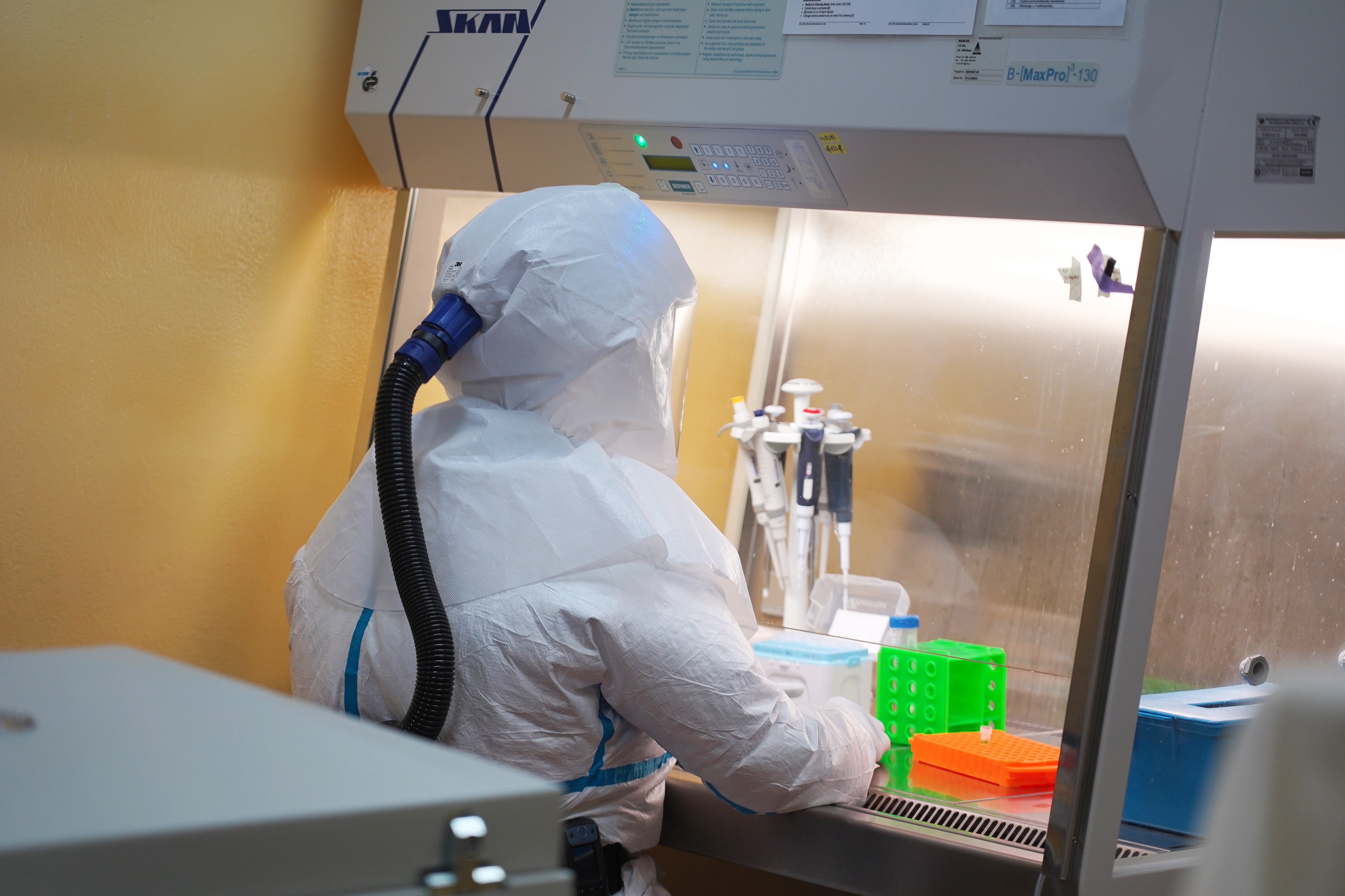

There are four biosafety levels; the higher the level, the more dangerous the pathogens you are working with and the more extensive the safety measures. In a level 4 high-security laboratory, for example, you wear a full protective suit and are supplied with separate breathing air. In a standard laboratory of a small biotech company, on the other hand, a lab coat, safety goggles and gloves are sufficient, depending on the regulations. Extreme caution is required not only when entering, but also when leaving the facility: nothing that could be contaminated must be allowed to escape.

What does a biosafety expert deal with?

Gesche: With biological hazards. These are organisms or biological materials that can pose a risk to humans, animals or the environment. These include certain bacteria, yeasts, protozoa, parasites and their infected hosts. The latter can also be insects, for example mosquito species that transmit malaria. In general, biosafety-relevant organisms can be genetically modified, pathogenic or alien organisms. Our aim is to ensure the safe handling of these organisms and to avoid any release, spread and infection.

What are typical projects that you work on?

Gesche: We advise research institutes, companies, authorities and organizations, as well as architecture and planning offices. As a rule, we support our clients in the structural and technical design of biosafety-relevant laboratories and high containment facilities. We naturally coordinate with other safety areas, such as fire engineering. In addition to safety and security, we also consider the efficiency of the planned processes. In Poland, for example, we had a project involving the renovation of a high containment facility that never went into operation. We used a gap analysis to show what needed to be improved and supported the institute in designing the renovation in such a way that a functional, safe high containment laboratory would be created in the future that would meet its needs.

We often also accompany the structural implementation and commissioning. We not only inspect the facility and all safety-relevant equipment, but also the work processes and the safety culture of the employees. If necessary, we develop operational safety concepts and train employees on site.

Sometimes we check existing high containment facilities in a compliance audit. In Northern Europe, for example, we conducted an on-site audit at a polio vaccine manufacturing company to determine whether the facility complied with legal requirements and the international state of the art in safety technology.

Is there any form of tolerance at all in biosafety?

Gesche: There is no tolerance for the project-specific defined safety targets, they must be achieved. In biosafety, the safety targets are based on three pillars: national laws, international standards and best practices, and the respective project risk analyses. However, there is tolerance in the way we achieve these goals. Openness and a certain degree of flexibility are required in order to find customer-specific solutions. European standards are not always transferable to other countries; sometimes the climatic or technical possibilities are different or we have to take cultural traditions and religious conditions into account. In some countries, for example, the desire to wear a hijab must be taken into account when we determine the protective equipment together with the customer.

Is the team currently working on a project in which openness is key?

Gesche : We have a project in India where we have to find solutions with an open mind. We are planning to build a veterinary institute there to develop vaccines, for example against foot-and-mouth disease. The effectiveness of such vaccines must be tested on animals. In the case of foot and mouth disease, these are cows. All over the world, the cows would be killed after the tests and the carcasses would have to be decontaminated within the high containment area, as potentially infectious materials, including animal carcasses, must be inactivated. It is essential to prevent pathogens from spreading to the outside world. However, cows are sacred in India and must not be killed. A concept is therefore required for how these cows can continue to live, for example on a specially designed type of "farm of mercy" on the grounds of the institute. Whether this will be possible is still unclear. However, an open mind is needed to tackle such issues.

Has the coronavirus pandemic had an impact on your work?

Gesche: Yes, absolutely. Since the pandemic, the need for high-security laboratories for diagnostics and the production of vaccines against highly infectious and pandemic pathogens has increased worldwide. Many countries have realized that they are dependent on other countries and would have supply deficits in an emergency. We are providing advice on this in projects in Africa and South East Asia.

Are there other aspects of biosafety that have become more important?

Gesche: An increasingly important topic in biosafety is AI, its effects, dangers and its use. Another aspect that is receiving increasing attention is biosecurity. This is about preventing the misuse and theft of pathogens or the data associated with them. This aspect has already found its way into Swiss legislation, and its topicality is reflected in a new international guideline on biosecurity published by the World Health Organization in July 2024. Ultimately, it is about dual use. This refers to the possibility that one and the same substance can be used for peaceful purposes, but in the worst case also for weapons and bioterrorism. We have always highlighted biosecurity in every risk analyses. However, we have noticed that smaller companies are now also addressing this issue on their own initiative.